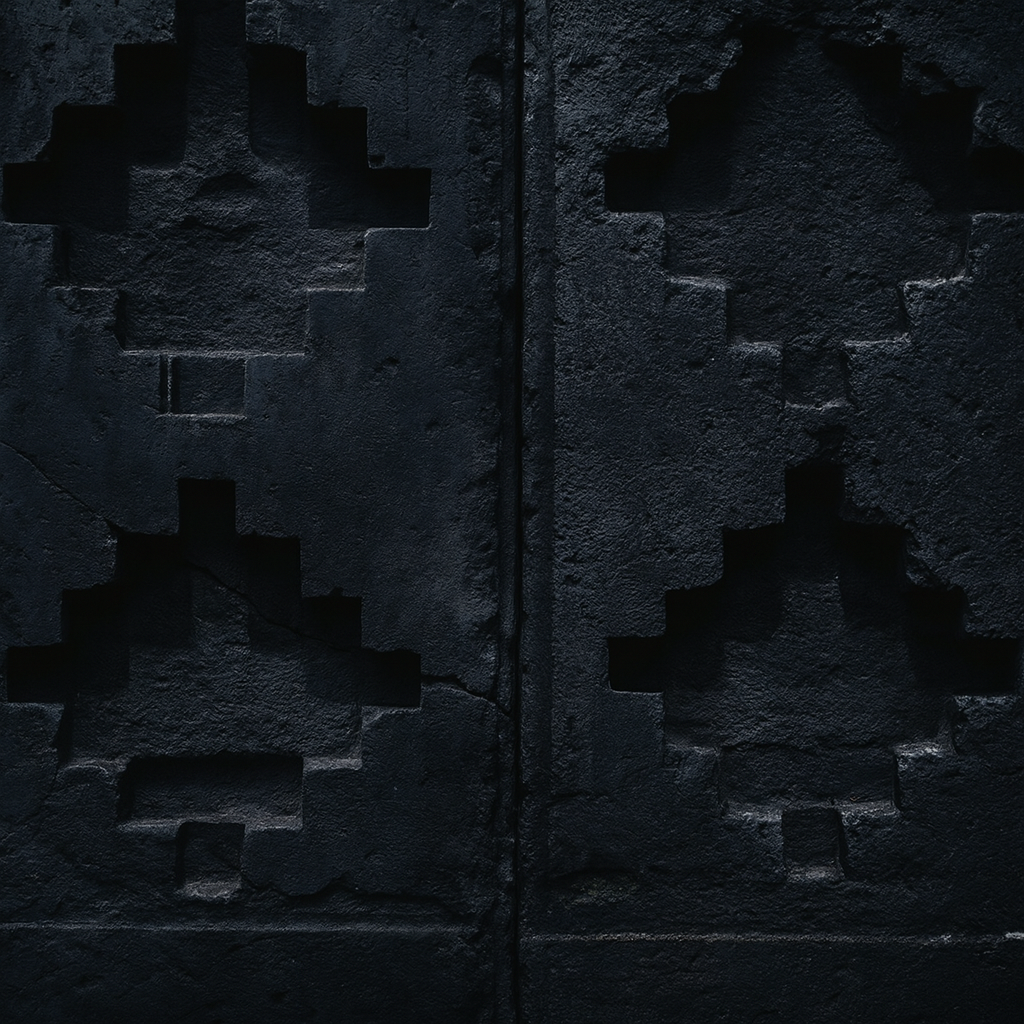

Forged in the heart of the Bolivian Andes during the early 1990s, Alcoholika La Christo emerged from La Paz as one of South America’s most provocative and visionary metal acts. Conceived by Viko Paredes, the band was born with a rebellious spirit—melding the raw power of industrial and gothic metal with the ancestral echoes of Andean mysticism.

Their debut album Agonika (1995) introduced a dark and experimental sound that broke all expectations within Bolivia’s scene. With the release of La Christo, the band’s aesthetic grew more theatrical and intense, exploring themes of death, sensuality, and inner conflict through haunting soundscapes and visceral performances.

The next release was in 1998, La Christo marked a decisive evolution in Alcoholika’s sound and concept.

Blending dark atmospheres, industrial rhythms, a gothic identity and lyrical explorations of spiritual conflict, desire, and death. .

Visually and sonically, La Christo turned Alcoholika into more than a band, it evolved into a multidimensional concept — fusing music, performance, and visual expression into a single entity. The record explored spiritual tension, desire, and sacrifice through theatrical arrangements and gothic atmospheres. It established the visual and philosophical pillars that would define the band for decades

In 2001, Toxicnology opened a new chapter. The band incorporated Andean instruments, chants, and native rhythms, creating a distinct hybrid later known as Andean Folk Industrial Metal. The result was a sound that blended the mechanical pulse of industrial music with the ancestral spirit of the Andes. The album’s international reissues in Europe, Mexico, and the United States in 2006 expanded the band’s reach, earning them a cult following among fans of experimental and ethnically infused metal.

With Nación Alcoholika (2007), the group took a bold step into cultural and ideological territory. The album became a declaration of Bolivian identity and artistic rebellion, merging industrial aggression with ritualistic energy. Its lyrics and sonic textures spoke of social conflict, heritage, and defiance. The record’s inclusion in the soundtrack of ¿Quién mató a la llamita blanca? connected Alcoholika’s underground force to a wider cultural moment in Bolivia’s modern history.

The following year, Santificato (2008) brought introspection and the fragility of existence. Songs like “I Am Bolivia,” “Frío,” and “Dramatik Tragik Dance” revealed an emotional balance between aggression and spirituality, showing Alcoholika’s ability to move from the visceral to the transcendent without losing its raw power.

After several years of silence, Alcoholika La Christo returned with Delithium (2017), symbolizing a creative rebirth. The album reaffirmed the band’s connection between the ethnic and the industrial, between past and future. Its collaboration with the legendary Andean singer Luzmila Carpio on “Warmikuna Yupaychasqapuni Kasunchik” united two cultural worlds — the sacred voice of the Andes and the relentless rhythm of post-industrial metal — in one unforgettable composition.

Today, Alcoholika La Christo stands as a pillar of Bolivian rock and metal history, a band that broke through every boundary and convention. Their fusion of industrial brutality, gothic beauty, and ancestral spirit has built a soundscape that is both deeply and rebelliously human.

More than three decades after its creation, Alcoholika remains a symbol of artistic resistance. It carries the soul of the Andes into the global metal scene. On stage, the band transforms performance into ritual: smoke, light, and sound converge into an experience that feels both sacred and defiant.

From the high altitudes of La Paz to international stages, Alcoholika La Christo resonates as a reminder that art, when born from truth and struggle, can transcend borders, time, and death itself.

The spirit of the Andes still screams through their amplifiers, eternal, electric, and alive.